Reflecting on European One Health project COHESIVE

An interview with Kitty Maassen

Publication date 26 October 2022

Kitty Maassen has been with the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) for eleven years now. In addition to her vital work as head of the Animal and Vector department within the RIVM Centre for Zoonoses and Environmental Microbiology, she also served as coordinator for COHESIVE, a four-year project in the framework of the One Health European Joint Programme. COHESIVE focused on developing guidelines and tools for One Health approaches to signalling, assessing and controlling zoonoses. These resources can facilitate international cooperation and improve pandemic preparedness. Looking back after the end of the project, she reflects on accomplishments and challenges as well as hopes for what can be achieved with One Health approaches in future.

Scaling up response to outbreaks

“When we embarked on this initiative, OH EJP chose me to take the lead in coordinating COHESIVE. As department head of Animal and Vector, I had a strong background in zoonoses: infectious diseases that can be transmitted directly or indirectly between animals and humans. I had been working on the Zoonoses Structure in the Netherlands – designed to effectively scale up zoonosis management in response to new developments.

“In essence, the Zoonoses Structure is a human-veterinary integrated risk analysis system. The first step is signalling the potential issue and followed by scaling up risk assessment, management and communication as appropriate and necessary. It was instituted following the Q fever epidemic as well as outbreaks of other zoonotic diseases. The best-known example around that time would probably have been the 2003 outbreak of avian influenza.

“Obviously, the best-known zoonosis right now is SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. But the zoonotic aspect of the pandemic was over quickly; most likely there were one or two spillovers, and then human-to-human transmission took over. In that respect, it is similar to Ebola: the outbreak is sparked by a spillover event, but is then transmissible between humans. Many zoonotic diseases cause a one-time spillover, but then stop there. Q fever, for example, is not transmitted from one person to another. In these situations, the source is either from animals, or from food, not from other people.”

Zoonoses Structure1. Signalling the potential issue

2. Analysing the risk

a. Risk assessment

b. Risk management

c. Risk communication

3. Scaling up the response

Multidisciplinary risk analysis

“A risk analysis system for communicable diseases already existed after the SARS outbreak in 2003, but a parallel structure was established for zoonoses, based on a multidisciplinary One Health approach. The combination of humans and animals is already an inherent part of the concept; that meant that the structure always included partners from veterinary medicine as well as experts and specialists in human medicine. Initially, the plan was to focus primarily on emergent threats. As the structure took shape, however, additional groups were formed, broadening the scope to foodborne diseases, environmental factors and antimicrobial resistance.

“In the multidisciplinary risk analysis system for zoonotic diseases used in the Netherlands, the roles, tasks and responsibilities are clearly defined. The participants hold monthly meetings to signal potential risks (sometimes referred to as 'hazard identification') and inform each other of relevant trends and events in their respective specialisations.

“Until a few months ago, I chaired the Signalling Forum for the One Health Risk Analysis System (OHRAS) used in the Netherlands. The ministers of the Dutch government sing the praises of our national OHRAS, but a joint strategy across Europe requires a well-structured One Health approach in all those countries. That means that we needed to disseminate that way of working and ensure that other European countries also adopted a comparable system. I fully support that course of action.”

Crisis-driven improvements

“Due in part to the BSE crisis in the 1990s, the UK was a frontrunner in developing a system for multidisciplinary risk analysis: the Human Animal Infections and Risk Surveillance Group (HAIRS), which has met monthly since 2004. The process was comparable to what happened here after Q fever and avian flu: a potential health crisis involving a zoonotic outbreak was followed by an evaluation of what factors contributed to the crisis, leading to suggestions for improvements and resulting in a system for multidisciplinary risk response.

“In the Netherlands, our human risk analysis system was used as the basis for designing the OHRAS. That is definitely not the only way to do it, however. There is no blueprint; each country has its own responsibilities and systems and import standards. There are local and regional differences: weather and climate patterns, which diseases are most prevalent, how the country's government ministries and portfolios are structured, the flows of funding and requirements for accountability… Not to mention what is already in place in a specific country and what can still be added. To some extent, each country has to come up with a custom design tailored to their own context. We can offer guidelines, but there is no rigid protocol guaranteeing a fool-proof system within two months. And it does take time, especially when political will is not there yet.”

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), a neurogenerative disease that affects cattle, was first found in the United Kingdom in the 1980s and 1990s. The disease then spread to humans through the consumption of tainted beef. In the 1990s, this animal-to-human transmission caused an outbreak of what came to be known as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (v-CJD) or ‘mad cow disease’. The resulting public health crisis led to a ban on British beef exports for many years.Various aspects, various partners

“The COHESIVE project involved a consortium of 21 partners in 12 countries in the context of the One Health EJP. Unsurprisingly, different organisations within the consortium focused on various aspects, each with its own emphasis. The project was divided into four work packages: coordination, the guidelines and online tool, cross-border improvements and lessons learned, and IT tools. Throughout the project, there was a strong focus on cooperation and connection.

“Needs assessment was obviously an important starting point for the guidelines. The Signalling Pathway Analysis, a study conducted in six countries that included interviews with relevant parties, yielded results that confirmed our previous expectations. First and foremost, both formal and informal routes for sharing information are key to signalling potential risks. It is absolutely vital for data sharing to be facilitated. Parties need to build trust and familiarity, to know each other and know who to contact.

“We live in a world that is very connected. The products we use and consume move through many different sectors before they reach us. One of the resources we wanted to develop in the COHESIVE project was IT tools to support signalling, risk assessment and risk management, and other One Health activities. Examples include a web-based decision support tool for One Health risk assessment, which offers a starting point to identify which risk assessment tool is best suited to analyse your specific situation: qualitative or quantitative, long-term or short-term risks, etc. We also wanted to make it possible to compile information from a wide range of sectors, combining all the data in a single database or linking different databases in such a way that the data can be easily accessed and utilised.”

Connecting and combining data

“Let's take foodborne diseases as an example. The recent outbreak of Salmonella in chocolate made it necessary to access data about chocolate distribution, hospital admissions, points of sale and production factories. All that data is stored in different systems across national borders, but it is all relevant to tracing the source and controlling the outbreak. The IT tool that was developed for this purpose is the COHESIVE Information System (CIS), which focuses specifically on the connections between data from different sectors. Data compilation is centralised, national and cross-border, facilitating tracing efforts throughout the supply chain.

Modular tracing in the food chain

“Returning to the Salmonella example, it was not only important to identify that the bacteria had been found in chocolate, but also to trace the point of sale and the production location. Similar to pharmaceutical traceability, where a specific batch and lot number makes it possible to trace and recall a potentially faulty shipment of medication, this makes it possible to track down a potential hazard once the general direction has been determined. It should be noted that data compilation becomes more difficult in cross-border supply chains, especially involving ingredients that are renumbered during transhipment.

“Another IT tool developed in the context of the COHESIVE project is the FoodChain-Lab web application, which can be used to trace a specific food product back to the source and forward to the point of sale. The concept already existed, but we developed it to expand its usability. We wanted to make it modular: adding functionality by integrating various data sources as well as analysis and reporting modules, which would expand traceability. In addition, it was important for this tool to be web-based. The advantages: no need to install software, accessible anytime and anywhere, and always using the latest information. The result was the free and open-source FCL Web.

“A simulation exercise was executed, with various countries participating. The idea was to simulate an outbreak based on a foodborne disease, and they were using this tool as part of the exercise. One of the interesting aspects is that different organisations within each country were working together. I am looking forward to seeing the feedback that comes out of that, and I hope that the tool will continue to be used.” (Eds: Although the official evaluation is still pending, initial feedback was positive.)

Challenging collaboration during COVID-19

“Of course we faced some unexpected challenges due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Co-creation processes really suffered under the coronavirus measures. The guidelines were a co-creation product that was originally intended to be designed through in-person workshops. One of the most significant ways that COVID-19 affected the COHESIVE project was that we were not able to move forward to real implementation during the four-year period of the project. That would have been even better.”

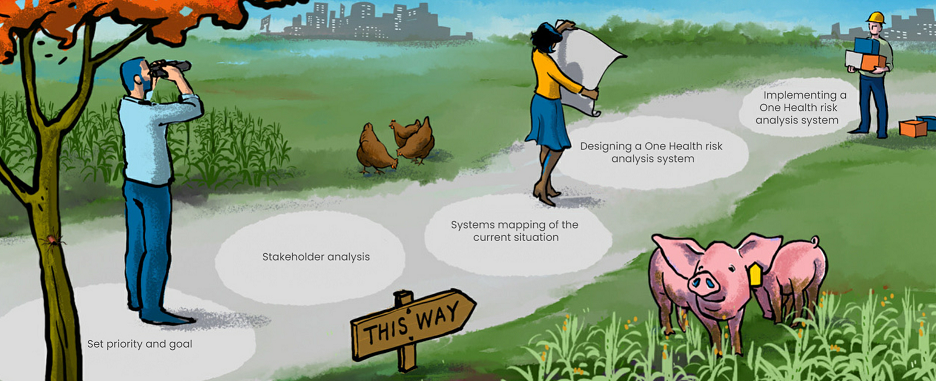

Five steps to OHRAS

“The steppingstones we designed to help countries get started are basically a roadmap in five steps. Step 3 was a systems mapping workshop, which was designed for multidisciplinary, in-person sessions on location in each country, generally involving about 20 to 30 people. The first workshops were scheduled for March 2020, but that obviously had to be postponed. Last year we were able to hold workshops in Portugal and Norway, during the COHESIVE project itself.

“A few more workshops were scheduled after the project had technically already ended – Denmark and Sweden, for example. Denmark has already adopted a fairly far-reaching One Health approach, and there is government support and political will to make it happen. We saw that the people there are already accustomed to the idea and enthusiastic about embracing it, but still very critical about their own situation. It was also nice to see that we are still developing too; the workshop gets better and better every time.”

1. Setting priorities and goals:

- Defining the scope of which risks are addressed: emergent, foodborne, antibiotic-resistant, one specific disease, etc.

2. Stakeholder analysis:

- Identifying which government bodies are involved and which other sectors and parties play a role

- Building trust and cooperation

3. Systems mapping workshop:

- Sitting down together to explore what the current system looks like

- Identifying gaps, strengths, areas for improvement

4. Designing a One Health risk analysis system:

- Facilitating discussion (using the simple web app)

- Defining the desired end result

- Coming up with an initial design

5. OHRAS implementation:

- Reaching consensus

- Drafting an action plan

- Implementing the plan

Steppingstones to a One Health Risk Analysis System

Prioritising preparedness

“Crisis always accelerates the timeline. We also had to experience a crisis before our government authorities considered it a major priority. Governmental support and political will are often lacking in countries until an urgent issue makes it unavoidable. As a result, it is much more difficult to achieve structural change during peacetime and in non-crisis periods. Even so, an effective response to emergent outbreaks can be significantly improved by having an implementation structure in place that is deployment-ready and can be scaled up as needed. My work focuses primarily on that preparedness side of the equation.

“The COVID-19 crisis has raised public awareness of the potential risk of infectious diseases, and particularly zoonoses. But as a person working in public health, I am aware of the ‘prevention paradox’: if you do your work very well and are able to prevent risks from developing, people never get to see that you did a good job.

“We would like to see a stronger emphasis on prevention, especially on the veterinary side, to prevent that shift to human transmission. But public attention ebbs away after a while. After the first SARS outbreak [in 2003], many countries introduced systemic changes, but funding eventually dried up because that threat was gone. If COVID-19 is really gone at some point, or if it becomes a lower-priority issue, it may be very difficult to maintain a focus on this problem. It is harder to find funding for a disease that no longer has a high infection rate. COVID-19 has led to an enormous boost in attention and funding, but for how long? These systemic changes are vitally important to our ability to address emerging zoonotic threats in the future.”

Future impact

“The COHESIVE project has ended now, although a few more workshops will still take place. It’s good to see that the outcomes are resulting in changes and improvements, in other countries and in the Netherlands. My driving passion is clear: we made such wonderful things in the project, and now I want people to use them in actual practice.

“My hope is that COHESIVE has been able to make some small contribution to One Health cooperation, and that a number of European countries will use the guidelines to achieve changes in how they work together. It would be great if they were able to set up a national OHRAS, but it would already be a good development if they went through the steps and implemented the resulting plan. That would improve European preparedness for zoonosis events and enable a cross-border approach. I also hope that countries will adopt some of the IT tools that were developed, which will facilitate an effective outbreak response.”